When you go to a doctor’s office, whether for an annual checkup or for specific symptoms, your doctor might ask you to provide a urine sample for testing at a clinical lab. The test can check for kidney disease and conditions that affect kidney function, such as diabetes and urinary tract infections.

To diagnose these conditions correctly, your doctor needs accurate measurements of key compounds in urine. Now, thanks to a new standard reference material (SRM) from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), those measurements are about to get more accurate and precise. SRM 3666 is a new human urine standard, the first of its kind, that contains carefully measured amounts of a protein called albumin and another important molecule called creatinine. The standard will improve clinical measurements and support decisions for diagnosing kidney disease.

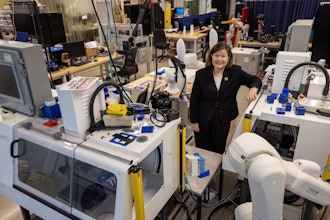

“We need precise clinical measurements so clinicians can make accurate decisions. This SRM directly impacts the health of individuals and the quality of care they receive,” said NIST chemist Ashley Beasley Green. “It’s hard to determine the risk of kidney disease with inconsistent test results.”

To check the health of your kidneys, clinicians look at the ratio of albumin to creatinine. Albumin is a protein created in the liver, and creatinine is a small molecule and waste product that is filtered by your kidneys out of the body through your urine.

Albumin circulates through the bloodstream and helps keep fluid from leaking out from your blood vessels. It also transports other compounds, such as hormones and vitamins, throughout the body. Since the primary function of kidneys is to filter blood, small amounts of albumin can be expected in the urine. But when high levels of these compounds are detected in urine, this could mean your kidneys aren’t functioning properly.

Standards exist to support measurements of creatinine; however, there are no standards for albumin in human urine, increasing the risk of inconsistent measurements from one lab to the next, hence the need for a standard.

The new SRM consists of four vials of different levels of albumin and creatinine. The four levels represent the clinical ranges of albumin in urine, from normal levels to those indicating disease. To develop the human urine-based material, Green collaborated with the global clinical community to obtain urine samples from patients with kidney function that ranged from normal to having preexisting disease. The SRM comes with a data sheet that gives accurate measures of how much albumin and creatinine are in each vial.

Laboratories that test urine samples can use the SRM for quality control. Researchers can run the material through their instruments, and if their results match the numbers on the data sheet, then they can have greater assurance their instruments are working correctly.

Until now, the standard for albumin was based in serum, a clear liquid component of blood, and not human urine. “The ideal standard is always in the same material as the clinical sample. If you send a urine sample to a lab, you expect the quality control material to be the same,” said Green.

This work is part of a larger program, called the Urine Albumin Standardization Program, that has been active for over a decade to build these reference materials. But the work is not done after the SRM is released. International studies, such as interlaboratory comparisons that use the SRM, will be conducted to further confirm that the material meets the needs of the entire community, from clinical labs to assay manufacturers.

In addition, the implications of the SRM go beyond improving the accuracy of clinical measurements. It also can have future impacts on clinical guidelines and improving the framework of how doctors diagnose and treat patients. “This SRM is the first of its kind and will allow better guidelines for patient care. It stands to have a tremendous impact,” said NIST chemist Karen Phinney.