Paula Nieto-Morales recalls the puzzled looks on her parents' faces when she told them she wanted to become a neonatologist. She was 5 years old.

"I was so little! And they asked, 'Where did you learn that word?'" said Nieto-Morales, who was born and raised in Colombia.

She likely picked it up while watching television, mostly nature and medical documentaries. Flashed on the screen were images of babies and the word "neonatologist," a doctor who specializes in the care of babies born prematurely or with congenital disorders.

Nieto-Morales, the daughter of physicians, has had a lifelong interest in learning about newborns and science. It carried through to her time at the University of the Cumberlands in Williamsburg, Kentucky, and now as she seeks a doctorate in biomedical sciences at Florida State University College of Medicine in Tallahassee.

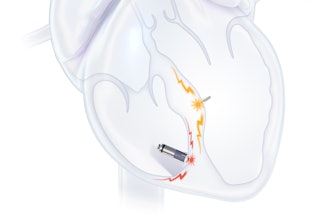

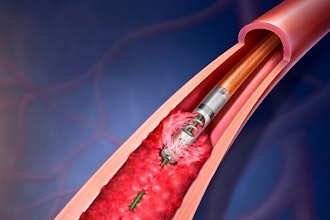

At FSU, Nieto-Morales studies diseases of the cardiac muscle, or cardiomyopathies. It has inspired her to pursue a career in pediatric cardiology.

"I have always been fascinated by the heart and the fact that it never stops," she said. "It's always working" – just like Nieto-Morales, who seemingly is always looking to explore new ideas and opportunities.

In 2013, at age 16, she moved to the United States by herself after earning two scholarships, including one to play collegiate tennis.

After graduating in 2018 with bachelor's degrees in chemistry and biology, she moved to Atlanta to work as a contractor with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections.

The CDC campus is about a five-minute walk from the Emory University School of Medicine. Soon after arriving in Atlanta, she contacted Emory to learn about its medical school. Nieto-Morales connected with Dr. David Elwood, who invited her to be part of a hospital program that included checking in on patients and observing the first surgery case of the day.

Nieto-Morales jumped at the chance to join medical residents and attending physicians, listening as they discussed cases and asking many questions. It had to be on her own time, so she would arrive by 6 a.m. and leave in time to get to the CDC three hours later.

"Some of these physicians, they love to teach," said Nieto-Morales, who considers Elwood a mentor. "They're used to having a lot of medical students, so that's probably why everyone thought that I was a medical student."

Then in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Medical facilities in the nation desperately needed health care workers. With her CDC contract coming to an end, Nieto-Morales had two job offers: Work at Emory as a lab technician or become a clinical laboratory scientist contractor with the CDC's COVID Global Response Team.

The CDC position would deploy her to the Oklahoma State Department of Health for nine months to support testing capabilities. Joining Emory would mean staying in familiar surroundings at a time of uncertainty while moving a step closer to medical school.

Nieto-Morales decided to head west, feeling a duty to respond to the crisis. By the end of the deployment, she felt prepared to pursue a career in research and medicine. In August 2021, she started the doctoral program at FSU, where she currently works in the lab of Dr. José Pinto, a professor in biomedical sciences who, along with colleague Dr. P. Bryant Chase, mentors Nieto-Morales.

"She's the type of student who thrives on challenges and constantly seeks new opportunities to learn and grow," Pinto said. "You have to keep providing her with tasks and projects because she's always eager to take on more and push her limits."

Nieto-Morales' research-centric path to medical school isn't typical, but it's all going according to her plan. She's on track to finish her doctoral program in the spring of 2026 and plans to start medical school that fall. She described her goal as becoming a "physician-scientist pediatric cardiologist who performs bench-to-bedside research and patient care for children diagnosed with heart disease."

Nieto-Morales has volunteered as an ultrasound technician at a women's pregnancy center that works with under-resourced populations to confirm fetal heartbeat and intrauterine pregnancies. She's also a scholar in the American Heart Association's National Hispanic Latino Cardiovascular Collaborative, a mentoring program that promotes the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke within the Hispanic community. Pinto encouraged her to apply, she said.

"He is not a physician, but he talks about patients often, which I think is rare for a basic science researcher to care so much for patients," she said. "I think that's why we are a good fit. He sees the big picture."

An avid runner, Nieto-Morales is training for an ultramarathon. She loves to travel and recently learned new research techniques at a lab at Amsterdam University Medical Center in the Netherlands. This summer, she also spent time doing a clinical research internship at a biotech company in San Francisco.

"Paula wants to assemble the complete package as a physician," Pinto said. "Her goal is to be able to help everyone, to make a difference in her future patients' lives."