Patti Allbritton was born a little blue.

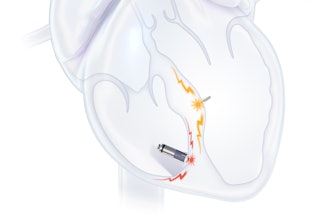

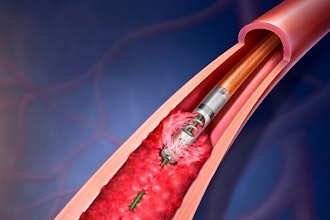

She wasn't particularly sad – it wasn't that kind of blue. She was born with a rare congenital heart defect called tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia, in which the valve that's supposed to control blood flow from her heart to her lungs never grew. Instead, her heart sent blood out through a set of collateral vessels. It got the job done but made her heart work harder and less effectively. This resulted in such poor oxygen saturation that it gave her fingernails and the skin around her mouth a faint blue tint when she was tired, a condition known as cyanosis.

At the time decades ago, Allbritton's parents were told nothing could be done to fix the problem, which was robbing their daughter of a typical childhood.

"As I grew up, I learned my limits," she said. "I played until I got tired and then I had to sit down to rest. Obviously, you know there's something different about you when everybody else doesn't have to do the same things you do."

Every year, her parents took her to see a cardiologist at Texas Children's Hospital in Houston, not far from her home in Pearland. Tests evaluated whether the complicated, roundabout job of moving blood from her heart to her lungs was functioning sufficiently.

"They would say, 'This is working; we're not going to mess with it,'" Allbritton said. "But as I continued to age and do more, I could tell my body was starting to let me know I was doing too much."

It was hard not to overexert. Allbritton was trying to live a normal life, despite her condition. She went to college. She got married. Because of her heart condition, doctors advised her not to get pregnant. So she and her husband, John, adopted a baby boy they named Joshua. She was frustrated that she didn't have the energy to do all the things new mothers typically do.

"Joshua hit 20 pounds at 6 months old. I couldn't hold him for very long," she said. "As a mom, you want to pick your toddler up and carry him around, and I didn't have that luxury."

As the years passed, the list of things she couldn't do grew. "He'd come home from school and want to tell me about his day and sometimes I couldn't even stay awake to listen to him," she said. "I just needed to nap."

By her mid-40s, Allbritton's oxygen saturation levels had dropped from the high 80s to the low 80s, sometimes dipping into the 70s. A healthy person has oxygen saturation levels in the upper 90s.

She found it harder and harder to do anything without feeling exhausted. "I couldn't even walk 100 feet without having to stop to catch my breath," she said. When she and her husband took her son to look at colleges, she had to sit out the campus tours.

Through it all, doctors continued monitoring her. They knew things were getting worse, but any surgical intervention carried more risks than benefits.

Then, in 2021, things changed.

Texas Children's Hospital had just opened a new adult congenital heart unit and brought in a team of dedicated surgeons and nurses. As a member of the volunteer patient advocacy team, Allbritton had even been asked to provide feedback on how to design patient rooms and menus.

With the added resources, "we felt better prepared to take care of complex patients," said Dr. Peter Ermis, the medical director of the new unit and – by then – Allbritton's primary cardiologist.

Allbritton's medical team began a year-long discussion about whether and how they could solve her problem.

"The issues going in were that there was a hole in the wall between the two chambers of her heart," Ermis said. "The heart had no direct connection to her lungs. She had extra vessels connecting her lungs to her aorta. We had to address all three of those problems. We had to close the hole, put in an artificial connection from the right side of her heart to her lungs, and close or disconnect the extra vessels because she wouldn't need them anymore."

"This takes a lot of pre-planning," he said.

Last year, when she was 48, all the planning paid off. The day-long surgery was so successful, her blood oxygen levels have risen to a robust 98. The first thing people noticed, she said, was that her skin changed color.

"After my surgery, so many people have commented to me, 'You're so pink now!'" she said.

Today, Allbritton exalts in doing all the things she thought she could never do. Little things – like walking across the parking lot to a store – bring her joy, simply because she was never able to do them before. She even joined an exercise class.

Best of all are the times she spends visiting her son at the University of Texas at Arlington. "We go and walk the campus all the time," she said. "Every time we go there, we walk."