An injectable hydrogel can mitigate damage to the right ventricle of the heart with chronic pressure overload, according to a new study published March 6 in Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Basic to Translational Science.

The study, by a research team from the University of California San Diego, Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University, was conducted in rodents. In 2019, this same hydrogel was shown to be safe in humans through an FDA-approved Phase 1 trial in people who suffered a heart attack. As a result of the new preclinical study, the FDA approved an investigational new drug application for the Emory and Georgia Tech researchers to start a clinical trial with the hydrogel in pediatric patients in the coming months, once institutional approvals are received.

In this case, the injectable hydrogel is intended for children born with a condition that leaves them with an underdeveloped, nonfunctional left ventricle. The disorder, known as hypoplastic left heart syndrome, comprises less than 4 percent of congenital heart defects. But it is responsible for 40 percent of deaths associated with heart defects in newborns. Patients with the disorder have a 35 percent survival rate.

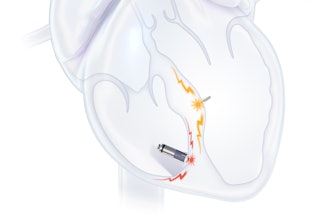

Current treatments consist of a series of three open heart surgeries all before the patient’s 5th year of life that reroutes oxygenated blood supply to the right ventricle. Pediatric patients who survive into childhood after surgery also receive medication and physical therapy, as well as a special diet. But this palliative surgery comes at a cost. In a healthy heart, the right ventricle’s job is to pump blood to the lungs; a job that entails dealing with blood at lower pressure and lower volume. When the right ventricle is forced to pump blood to the whole body, it develops several maladaptive traits, including overly large muscle and scarring. Eventually, the right ventricle begins to fail and patients will need a heart transplant.

“To the best of our knowledge, it’s the first time that an injectable biomaterial therapy has been evaluated to mitigate right ventricular heart failure,” said Jervaughn D. Hunter, the paper’s first author, who hails from Port Gibson, MS and earned his Ph.D. in the Shu Chien-Gene Lay Department of Bioengineering at UC San Diego.

In the rodent study, injecting the hydrogel into the right ventricle improved function and allowed the heart to tolerate increased blood pressure and volume. The treatment also slowed down the rate of tissue scarring and maladaptive muscle growth. The hope is that the hydrogel injection will increase the amount of time the patient’s heart functions.

“This isn’t a cure, but our goal is to prolong a patient’s life,” said Karen Christman, a bioengineering professor at UC San Diego and the paper’s corresponding author.

The treatment could also dramatically improve the patients’ quality of life, allowing better cognitive function and growth.

“They might be able to wait until they can get on an adult heart transplant list,” said Michael E. Davis, one of the paper’s senior authors and director of the Children’s Heart Research and Outcomes (HeRO) Center at Children's Healthcare of Atlanta and Professor of Biomedical Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University School of Medicine.

The hydrogel is made from cardiac extracellular matrix that is stripped of the cellular content through a cleansing process; dried and milled into powder form; and then liquefied into a fluid that can be easily injected into the heart. Once it hits body temperature and pH, the liquid turns into a semi-solid, porous gel that encourages the patient’s own cells to repopulate areas of damaged cardiac tissue and to improve heart function.

Positive results

Preclinically, the treament’s effects were first seen two weeks after injection.

Researchers in Christman’s lab prepared the hydrogel with tissue from both the right and left ventricles of the pig hearts. Interestingly, tissues on each side of the heart differ vastly.

Hydrogels from either side of the heart improved systolic function–the heart’s ability to pump blood. They also reduced heart muscle growth and scaring while prompting arteriole formation and growth. But overall, hydrogel derived from left-ventricle tissue was more effective. That’s likely because the hydrogel derived from right-ventricle tissue is richer in type 1 collagen, which may have led to the enhanced inflammatory response seen in the RV hydrogel treated group.

The injected hydrogel also affected gene expression, specifically pathways related to cardiac repair, including the development of the circulatory system, muscle structure and vasculature, as well as regulation of immune response and cellular response to oxygen-containing compounds.

Next, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, the children's hospital collaborating with Georgia Tech and Emory will start recruiting for a clinical trial investigating the treatment’s efficacy in newborns with hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

Funding for the research came in part from the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.