New research from the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience (IoPPN) at King’s College London in partnership with the Mayo Clinic and UNEEG medical, has found that an electronic device placed under the scalp is an effective and feasible means of accurately tracking epilepsy.

In a landmark study, published in Epilepsia and funded by the Epilepsy Foundation of America, researchers demonstrated that seizures can be tracked in the home environment, giving clinicians access to data that could have a dramatic impact on the way in which epilepsy is treated in the future.

Tracking epileptic seizures over time is challenging and relies upon a person keeping a subjective diary. It is an unreliable format, as people with epilepsy can experience seizures without realizing, due to impairment of consciousness and memory loss, or might misinterpret several symptoms as seizures when they are not. This is particularly important for those with treatment resistant epilepsy, who have ongoing seizures despite treatment with anti-seizure medication – known to occur in around a third of people with epilepsy.

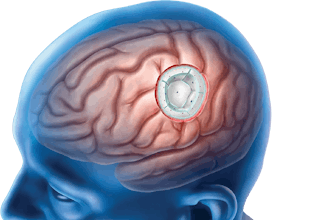

Novel subcutaneous electroencephalography (sqEEG) systems - consisting of a small electrode placed beneath the skin – have been proposed as a means of overcoming this challenge, but the feasibility, acceptability and overall clinical utility of these systems had not been tested until now.

sqEEG is an AI powered miniature implantable EEG for real life monitoring of people with epilepsy. It is about the size of a UK pound coin and has a small 10cm wire attached. Under local anesthetic, it is placed behind the ear beneath the scalp and the wire is directed to where the seizures are expected to occur. The sqEEG wirelessly communicates with an external recorder attached with an adhesive pad behind the ear and fixed with a magnet or clip from which clinicians and researchers are able to access the data.

This study recruited 10 adults with treatment resistant epilepsy from King's College Hospital and St. George's University Hospital. They were then asked to record as much data as they could over the course of 15 months, while also keeping a seizure diary and keeping track of their health and fitness via a wearable fitness tracker.

Over the course of the study period, almost 72,000 hours of real-world brainwave data were collected, capturing 754 seizures. Participants largely reported that the implant was acceptable and unobtrusive, with half recording for more than 20 hours a day.

Researchers analyzed the data and made several key observations. When comparing the electronic data to the participants’ diaries, the participants had only correctly recorded 48 percent of their episodes. Conversely, more than a quarter (27 percent) of episodes that they’d recorded in their diaries were not associated with seizure activity.

“It is vital that people with treatment resistant epilepsy are able to access the best possible care. This is made significantly more challenging by the fact that clinicians must rely on patient reporting to establish when episodes have taken place," said Professor Mark Richardson, Paul Getty III Professor of Epilepsy at King’s IoPPN and the study’s senior author. “Our study has been able to provide a vital and viable alternative to relying on self-reported episodes. A small tracker placed under the skin was able to detect seizures far more accurately than the participants themselves.”

Epileptic seizures can broadly be divided into three separate groups; non-convulsive with preserved awareness, non-convulsive with impaired awareness, and convulsive. The participants were required to note down the nature of the type of episode they experienced as well as when it took place. Researchers again found that the sqEEG system was able to more accurately track the type of seizure experienced versus the participants’ diaries.

This work was supported by the Epilepsy Foundation's Epilepsy Innovation Institute My Seizure Gauge Project.